Rangers take the lead as ‘eyes and ears’ of the Northern Great Barrier Reef

In the lead up to National Reconciliation Week (27 May – 3 June), James Cook University’s scientists are this week upskilling Torres Strait rangers to be the eyes and ears in protecting seagrass meadows in the northernmost part of the Great Barrier Reef.

In one of the country’s most comprehensive seagrass monitoring programs, Torres Strait Regional Authority (TSRA) and JCU TropWATER Centre are together training rangers from remote island communities to monitor seagrass meadows in the nation’s far north.

TSRA Acting Chairperson Horace Baira said Green Island off Cairns – home to vital dugong and turtle seagrass habitat – provided the perfect training ground.

“Combining ancient knowledge and modern science is critical for conservation as we face climate impacts across the Torres Strait,” Mr Baira said.

“The ocean is the lifeblood of the Torres Strait and bringing together all fields of expertise will help protect this precious natural resource for current and future generations.”

JCU’s TropWATER Centre seagrass scientist Dr Alex Carter said the rangers were critical in regional assessments of seagrass condition in Torres Strait.

JCU’s TropWATER Centre seagrass scientist Dr Alex Carter said the rangers were critical in regional assessments of seagrass condition in Torres Strait.

“This training week builds on a 15-year partnership that goes from strength to strength as it continues to grow with new monitoring locations added to the network,” she said.

“Traditional Owners are the eyes and ears on the ground and this ranger-led program provides the first warnings of any declines or changes in seagrass health.

“This allows for quick management responses and targeted research projects to protect these important seagrass meadows.”

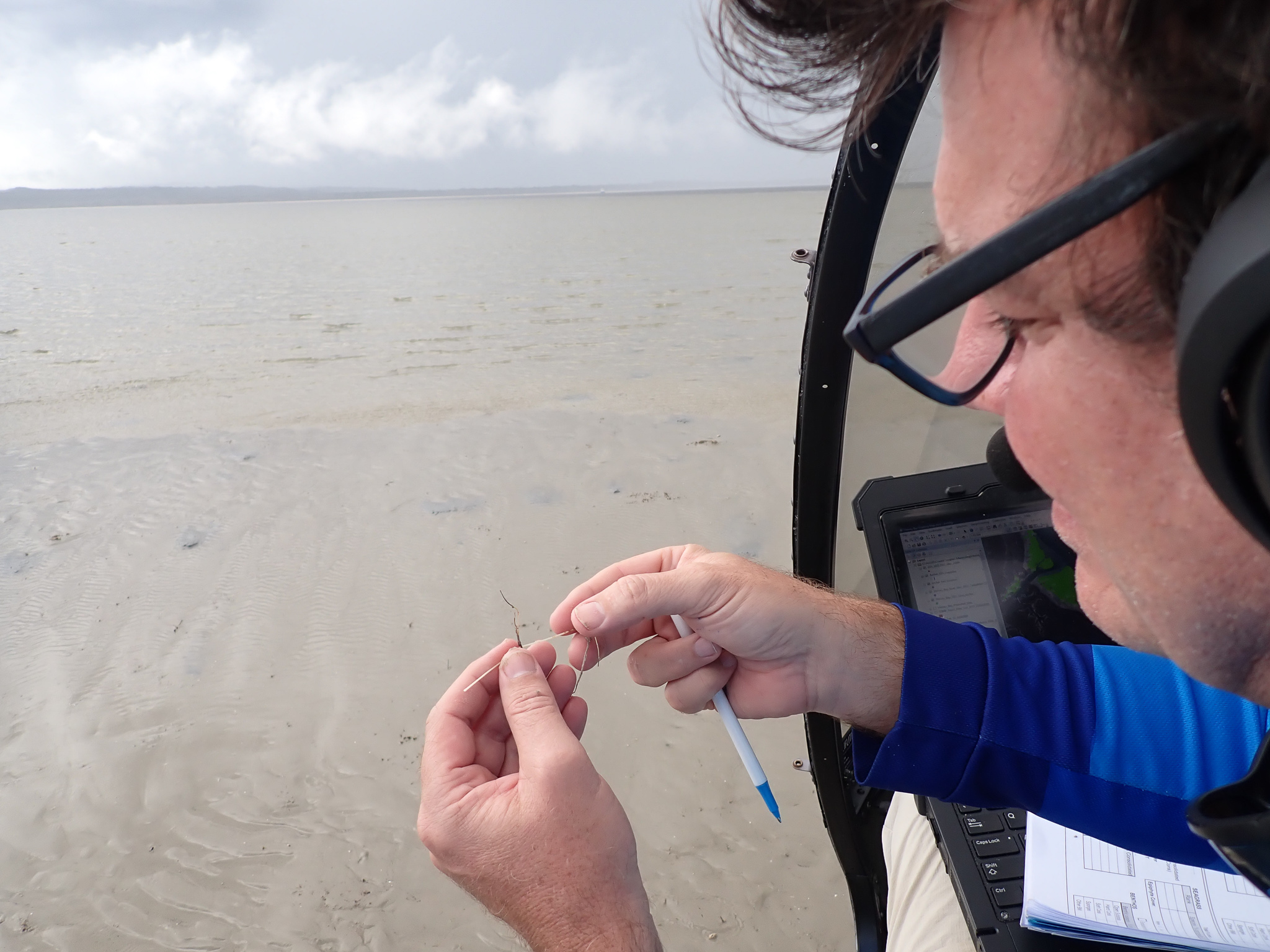

The four-day workshop, delivered by JCU scientists and TSRA, includes in-field training, species identification, and an opportunity to discuss results from recent research and monitoring projects to plan for future opportunities.

24-year-old Iama (Yam) Island Traditional Owner and TSRA Marine Biologist Madeina David said the training would support reef monitoring and results.

“Most people are unaware the Torres Strait is the most northern part of the Great Barrier Reef, home to the world’s largest dugong population and significant numbers of green turtles,” Ms David said.

“Working in partnership to value both traditional and western science gives our marine life and ocean ecosystems the best chance to survive and thrive.”

Meriam Traditional Owner and TSRA Senior Ranger Supervisor Aaron Bon said the training would build the capacity and knowledge of local Torres Strait Islander and Aboriginal rangers and boost conservation efforts across the Torres Strait.

“It will also assist Rangers and Traditional Owners to keep an eye on our reefs and seagrass meadows in the region and in doing so, we help protect some of the world’s most pristine and rich sea country,” Mr Bon said.

“Rangers will bring back skills, share learnings to support our important work on land and sea country in remote island communities and help us to make informed decisions around where we need to target our conservation efforts.”

TSRA employs up to 60 land and sea rangers across 14 Torres Strait communities to support employment opportunities for local people to combine traditional knowledge with conservation training to protect and manage land, sea and culture.

The recent 2021 Barra Bash at Lake Tinaroo was about angler participation and the elusive big barramundi, but emerging citizen scientists also investigated an unwanted species that has become established in the reservoir. The annual fishing tournament is a premier event on the north Queensland angling calendar and is run superbly by the Tableland Fish Stocking Society.

The recent 2021 Barra Bash at Lake Tinaroo was about angler participation and the elusive big barramundi, but emerging citizen scientists also investigated an unwanted species that has become established in the reservoir. The annual fishing tournament is a premier event on the north Queensland angling calendar and is run superbly by the Tableland Fish Stocking Society.