Back-to-back cyclones have exposed the Great Barrier Reef to extensive and persistent flood plumes from Ingham up to Cape York Peninsula, with terrestrial runoff lathering coral reef and seagrass ecosystems for weeks.

Scientists from James Cook University’s Centre for Tropical Water and Aquatic Ecosystem Research (TropWATER) have reported freshwater coral bleaching and seagrass damage, with flood plumes stretching more than 700km along the Great Barrier Reef coastline, and reaching some areas of the mid and outer reefs.

TropWATER water quality scientist Jane Waterhouse said we mustn’t underestimate the impacts of terrestrial runoff on marine ecosystems.

“Coastal and marine ecosystems do not like freshwater, let alone the sediments, nutrients and pesticides that are carried along with it,” she said.

“Seagrass meadows are highly vulnerable in these extreme events from both physical wave damage and the effects of low light from murky waters. Coral reefs can experience high stress resulting in isolated freshwater bleaching, and there is also a risk of macroalgae blooms out-competing coral reefs in the longer term,” she said.

Inshore ecosystems are critical for dugongs and turtles while also providing nursery habitat for key fish species, and high value recreational and tourist areas in the Great Barrier Reef.

Tropical Cyclone Jasper crossed north of Cairns in December, discharging in the order of 20,000 GL of freshwater – the equivalent of around 40 Sydney Harbours – into the northern Great Barrier Reef. Cyclone Kirrily, which crossed Townsville on 25 January, resulted in less rain.

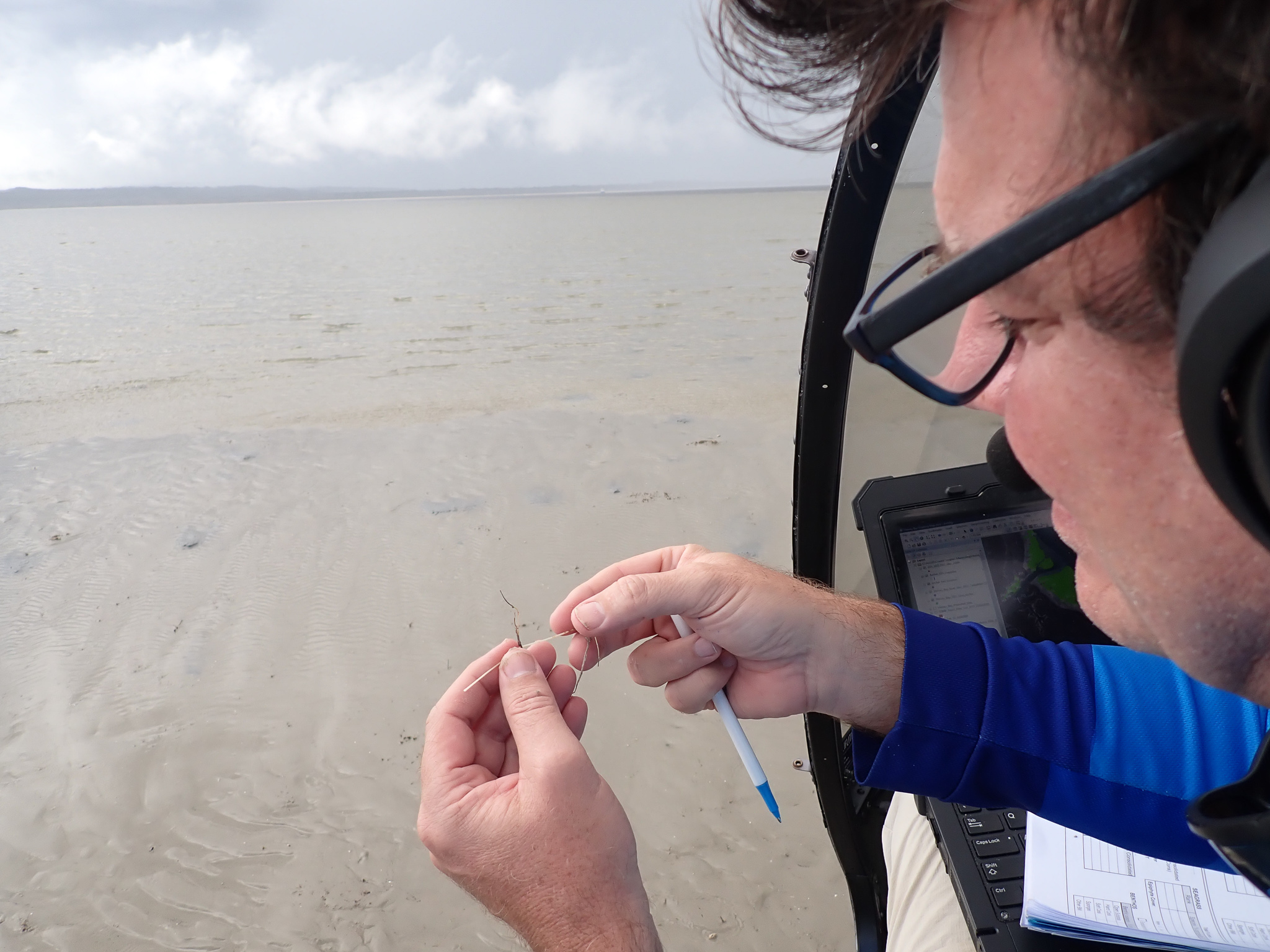

TropWATER scientists have been tracing and assessing the damage of flood plumes on marine ecosystems, sampling flood plume waters, analysing flood satellite imagery and surveying damage to seagrass meadows, as part of the Marine Monitoring Program.

TropWATER’s Dr Stephen Lewis said following Tropical Cyclone Jasper the team sampled flood waters from the Barron, Russell Mulgrave and Tully rivers, with preliminary observations suggesting elevated levels of nutrients and sediments in inshore coral and seagrass areas.

“A flood of this magnitude early in the wet season coincides with the end of cane crushing season, when fertilisers and pesticides have typically been applied to paddocks. This means there is a greater risk of runoff from paddocks,” he said.

“Many landholders are making extraordinary efforts to ensure they are minimising their off-farm losses of fertilisers and pesticides, while also undertaking local paddock scale water quality monitoring programs to understand runoff from their catchments.

“We need to support the farmers to continue these programs coupled with more water quality monitoring, especially when these events could become more frequent.”

Dr Lewis said a greater understanding of how sediments and nutrients travel from the land to the outer reefs is required to document exposure further offshore.

“Past monitoring on outer reefs indicates the presence of elevated nutrients linked to terrestrial runoff, which is supported by our satellite observations,” he said.

“But the current flood monitoring only samples waters in inshore areas, it doesn’t sample the outer reefs, and this is critical for understanding the impacts of terrestrial runoff on reefs further offshore.

“There needs to be more targeted monitoring to understand the connection between the catchments to the middle and outer reefs to fully understand the extent and impact of land-based runoff.”

Jane Waterhouse said understanding water quality is paramount for the long-term protection of marine ecosystems.

“It seems there’s no relief for the reef. This could be a new pattern emerging under climate change with relatively dry periods of mass coral bleaching events interwoven with periods of extensive flood events, with little to no time for marine ecosystems to recover in between disturbances.”

Marine heatwaves, cyclones, and flood plumes are weather events expected to escalate with the intensification of climate change.

“These pressures compound, hindering the recovery of ecosystems already grappling with prior disturbances, such as coral bleaching. Good water quality is essential for the recovery of reefs,” she said.

“The cumulative impact is unprecedented and deeply concerning. The true extent of the long-term impact remains largely unknown.”

Water quality and seagrass monitoring is part of Marine Monitoring Program, coordinated by the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, in partnership with JCU TropWATER, Cape York Water Monitoring Partnership, Australian Institute of Marine Science and the University of Queensland.

Link to images here.